BuildWitt: A Not So Brief History (PART 11)

Failure (the usual), Uncle Pete, and Mount Vernon

Welcome back to my likely inaccurate recollection of the history of BuildWitt!

If you missed PART 10, I discussed my anxiety, burritos, and catfish.

From one hell to the other… I kissed the railroad goodbye, which meant another year of engineering school.

Circuits

Am I still bitching about engineering school? Yes.

Growing up, everyone says hard work is the only thing between you and good grades.

It's inspiring and optimistic, but I discovered it's total bullshit, thanks to Circuits. Allow me to explain…

My degree required an engineering class unrelated to my major. The choice was between Thermofuilds and Circuits.

Hug a cactus or wrestle a kangaroo. Which was the less bad option?

I opted for Circuits since everyone said it was "easier." I hoped it would be like 4th-grade science. For the final exam, we'd sit with a 9V battery, wires, and a light bulb. If we made the bulb light up, we passed.

I was wrong. So wrong. REALLY wrong.

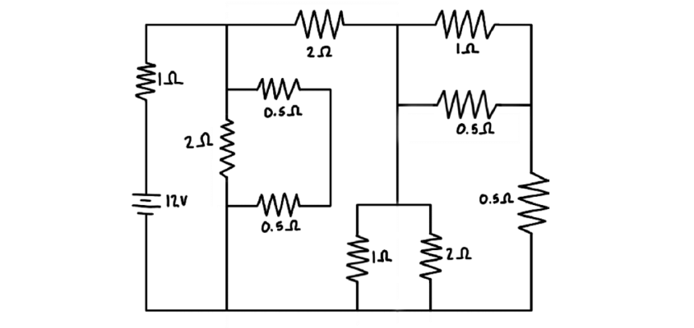

In Physics One (which, if you remember, I failed) and Physics Two (which I BARELY passed), we covered circuits on a surface level. If it was level one, Circuits class was level five.

The semester went as well for me as the Battle of the Little Bighorn did for Custer. It was a bloodbath. And it wasn't for lack of effort…

I went to office hours weekly, studied my ass off in the library, and diligently did every homework assignment. But no matter my effort, the magical properties of resistors, inductors, and capacitors alluded me to a near-catastrophic degree.

Passing came down to the final exam, and I anxiously awaited my final grade. While in a tent on the beach outside of Santa Barbara, I got an email saying grades were posted. "D." My heart sank.

BUT... I learned that since it wasn't part of my degree, "D" was passing. I've never been more proud of a grade. I worked hard for that "D."

That's what she said.

Construction School

I'd finished my prerequisites, meaning I reached degree-specific civil engineering and construction classes. I've beaten engineering to death, so let's explore construction...

In a way, my construction classes, like Heavy Equipment, Project Management, and Estimating, were a much-needed respite from the onslaught of Greek Letters in my engineering courses. But they also frustrated the heck outta me.

With my three summers of construction experience, I thought I was smart and knew better.

In Heavy Equipment class, we learned the theory of moving dirt—cycle times, fill factors, and equipment costs. It sounded great but didn't align with my field experience.

Our final project required us to run the numbers on building a job with scrapers. But based on the job, I thought an excavator and trucks would work better. My professor wasn't amused.

My other construction classes were building-centric. Since the GCs and homebuilders hire managers, they heavily rely on schools to feed their ranks. To grease the wheels in their favor, they drop COIN on construction schools around the US.

Our school was the "Del E Webb School of Construction." Guess what we estimated? If you guessed houses, you're right! But I didn't care about block walls or roofing. I wanted dirt.

Don't get me wrong—I'm the biggest fan of any construction program. If you're young and considering college, think of construction. EVERYONE had offers out of school with big salaries, company trucks, and cool projects to work on. And specifically, ASU's program is a powerhouse.

Uncle Pete

After three summers of working in the desert, I wised up and considered options outside the Southwest for my final summer.

As I rifled through my industry rolodex, I couldn't get one name out of my head—Kiewit.

I'd heard the legends of Kiewit for years. Famous for the biggest and baddest projects on insane schedules, they'd built American infrastructure since the 1800s. As a young buck, the allure was intoxicating.

They were far off until the Reno competition. But after meeting the big-time Kiewit judges, the door opened. I'd fulfilled my obligation with Skanska and was a free agent again.

I applied with their Northwest District, which covered Hawaii, Alaska, Washington, and Oregon—all nicer places than Glamis, California.

Thanks to my industry experience, they offered me a job in the fall, but I wouldn't know where I was going until the spring.

It didn't matter, but they did ask about my location preference. I responded Hawaii (duh), Washington, and Oregon. The wait was on...

The Office

In the meantime, I needed a new job during the school year. Thanks to my 9:00 bedtime, bartending was out.

I learned about Haydon Building Corp through an engineering friend who worked in their estimating department. He wanted something more engineering-specific and mentioned they needed a replacement.

Again, thanks to my field experience, I talked my way into the job even though I knew NOTHING about estimating.

Depending on my schedule, I worked at Haydon's Tempe office between 15 and 25 hours per week for the final two years of college.

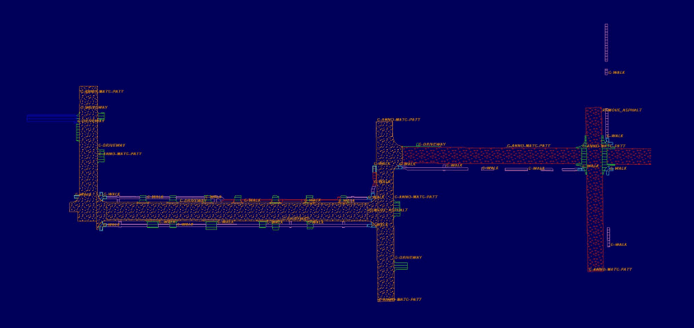

My task? Takeoffs...

For anyone who hasn't enjoyed working in a civil construction company estimating department, takeoffs exist to verify the plan quantities before submitting a bid.

Engineers don't always get things right despite what they may tell you. But their mistakes aren't their problem—they're the contractors'.

For example, say we were bidding on a new road project involving dirt work, asphalt paving, pipe, and concrete curb.

I'd get the project information (and CAD file, if I was lucky) on a flash drive and begin by organizing all the plans and specifications.

Then I'd build a computer model of the plans by joining the pages together and digitizing every line. CAD files saved us tons of time, but why would they make it easy?

Using AgTek software, I'd calculate the quantities of the dirt, pipe, asphalt, aggregate, and concrete. With the final numbers in hand, I'd compare them to the engineer's quantities and PRAY they were the same.

If they weren't, I double-checked my work, which was often the problem. But maybe 1 out of 100 times, the engineer's number was wrong. How we played our hand depended on the error. Estimating is all a game.

Estimating wasn't for me. It was incredibly depressing. We'd work for weeks on a project only to come in second or third the bid. If we lost, we'd throw everything in the trash and start over.

Project Tours

I'd become bold in asking for tours of construction projects I found interesting. I'd waltz into job trailers and ask for tours. Since I was a genuinely curious kid, most said yes.

I toured many large projects, but two come to mind.

The first was thanks to my new affiliation with Kiewit. They were re-lining a water transmission main and invited me to check it out. I didn't know what that meant, but you bet I signed up.

Weeks later, I found myself at the bottom of a "portal," or hole every few thousand feet above the water transmission main. They dug the hole, shored the earth, and opened the pipe for access.

As I stared into the black abyss of the pipe, someone handed me a cart, like the ones mechanics use to roll under cars. He grabbed another for himself and, without saying a word, set it in the pipe, laid down atop it on his stomach, and sent it into the pipe. Like a duckling, I followed.

The light vanished as we scooted further and further. We found the welders working feverishly to join the sections of steel liner together. No one above had any idea we were there.

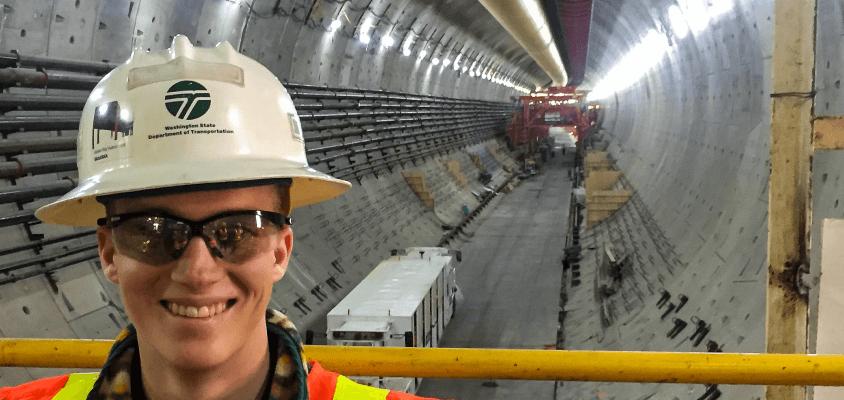

The second project was also underground but WAY bigger.

Years ago, Washington DOT discovered that the double-deck SR99 viaduct that ran around downtown Seattle along the water was in serious disrepair. Instead of replacing the eyesore with another eyesore, someone had the bold idea of tunneling under the city.

They bought what was at the time the world's largest tunnel boring machine, set it up at the edge of the city, and pressed "go." The machine ran into a small steel pipe not long after, ruining the entire cutting head. After billions of dollars in cost overruns, years of delays, and ongoing lawsuits, they got the tunnel back on track.

I planned to visit my friend DJ in Seattle and knew of the project from the news. Before the trip, we contacted Washington DOT and asked about a tour. We may have told them it was for our engineering school thesis.

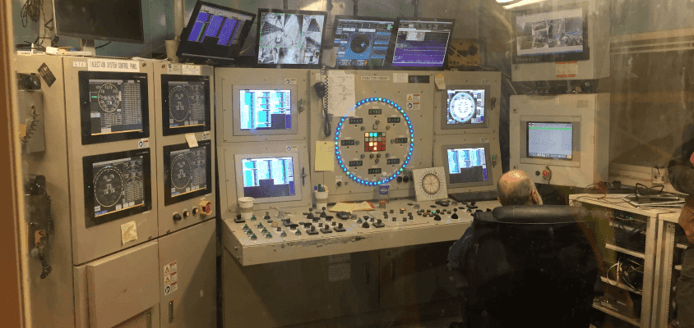

One, two, six, we were standing in the control room of Bertha, the TBM, deep under downtown Seattle. It was NEAT.

Mount Vernon

After the tunnel project, we drove north to check out Bellingham and Mount Vernon. It was April, so Tulip season was in full swing.

At this point, I still had no idea where I was going for the summer—it could've been anywhere from Oahu to Kodiak Island.

While driving through Mount Vernon, Washington (population 35,000), I got a call from a Kiewit project manager.

"Well, you're working with us in Mount Vernon, Washington, for the summer."

No shit…

Road Trip!

I barely escaped another year of school, and after packing my Toyota Camry with my clothes and camping gear, I hit the road north to Washington for the summer alone.

After a few days of exploring, I rolled into Mount Vernon as stoked as possible. I had nearly four months in this incredible place with mining machines and explosives!

But that's when my new reality slapped me in the face. Mount Vernon isn't flush with cheap living options for the summer. Without doing my due diligence, I booked a room in someone's house. It was cheap.

As I walked in, I found out why. My new roommate was an 80-year-old woman with cats galore.

But that's a story for another newsletter... Until then, stay dirty!

Dirt Talk Podcast

It’s not really a stretch to say that Ryan Neal is a @caterpillarinc equipment expert. After a career as an equipment operator, he joined the corporate arm of Caterpillar as a Senior Product Demonstrator Instructor. He worked his way up over the course of 16 years, and is now the Market Professional for Large Excavators. In addition to it sounding like an awesome job, it IS an awesome job. And thankfully, he was kind enough to stop by the BuildWitt HQ with his family a few weeks ago to chat on the podcast.

This week on Dirt Talk, host Aaron Witt and Ryan Neal discussed a number of Dirt World topics: nuclear/wind/solar energy, the challenges of communicating the importance of technology, and why it’s important to know that a good work ethic can be learned.

Vlog

Going where I've never gone before... Hawaii! Thanks to Goodfellow Bros. for taking us out here!

I’ll see you next week!